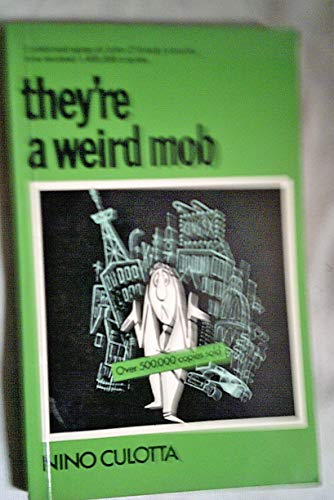

According to Jacinta Tynan’s introduction, O’Grady’s younger brother Frank, himself an author of historical novels, put £10 on the fact that John wouldn’t be able to write any sort of book and get it published. However, in the end, Nino assimilates easily, and the last chapter, which preaches for ‘New Australians’ to get out there and embrace the local way of living, of ‘ there is no better’, and not cleave to their own language and customs, seems incredibly and unfortunately dated.Īnother layer to this is that Nino Culotta is in fact not Nino Culotta at all, but the pseudonym of Australian Jack O’Grady (pictured left), who wrote They’re a Weird Mob on a bet. Nino rides a train next to a man who begins yelling obscenities at a nearby Italian family, who in turn mistakes Nino for ‘an Australian’ due to his northern features and begins complaining to him about ‘loody dagoes’.

There are moments that go towards demonstrating the hypocrisy of casual racism.

There’s also a real sense of charm and affection as Nino befriends his workmates, Joe, Dennis, Pat and Jimmy, who he finds to be ‘trangely profane and cynical and abusive, but basically such good men, delighting in simple pleasures’.Īs far as the immigrant experience goes, the novel is a light-hearted take, and very much of its time ( They’re a Weird Mob was originally published in 1957).

Comes up blue in the face, spittin’ sand an’ seaweed’) decides that they ‘must be speaking the technical language of lifesavers’, which he himself should quickly learn. Nino, for instance, listening to a group of lifeguards at Bondi (‘Wot about Marouba last Sundy? All on ‘e says, an’ falls for it himself. They’re a Weird Mob could easily be viewed as linguistically comedy of sorts, and indeed in this vein it’s as observant and wry as ever, putting a mirror just how impenetrable an exaggerated local dialect can be. Naturally, this leads to all sorts of misunderstanding and mischief. Rather, they appear to converse in a kind of ‘Australianese’, a mish-mash of flattened vowels, strung-together words, slang and subtle quirks of literalism. While Nino speaks almost perfect textbook English, the catch, as he soon discovers, is that most Australians do not. To do so, he bunkers down at a hotel in Kings Cross and eventually lines up a job as a bricklayer so that he can get to know ‘Working Australians’. Nino Culotta, both narrator and apparent author of the novel, travels from northern Italy on an assignment from his boss – to ‘write about what kind of people these Australians are’ for publications back home. In a way, They’re a Weird Mob reads just as much as a love-letter to the Australian language as it does as a paranorma of immigration and culture-shock in 1950s Sydney.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)